THIS POST INCLUDES:

1. Theoretical Foundations and Evidence-Based Practice

2. Practical Strategies for Curating and Organizing Your Library

3. Integrating Reflective Practice and Continuous Learning

4. Free Download Art Intervention Checklist

Theoretical Foundations and Evidence-Based Practice

A well‑curated library of therapeutic art exercises is far more than a collection of creative prompts. For the qualified or training art therapist, it is a living, evolving resource that reflects theoretical grounding, clinical responsiveness, and a commitment to ethical, evidence‑informed practice. Whether you work in private practice, community services, or organisational settings, a structured library enhances flexibility, supports supervision, and provides a foundation for session planning that is both creative and clinically sound.

This article outlines three essential pillars for building and maintaining such a resource, drawing on psychological theory, art therapy methodologies, and practical business management strategies.

The starting point for any art therapy intervention is its therapeutic intention. Without a clear theoretical frame, art activities risk becoming “arts and crafts” rather than targeted, intentional interventions. Aligning each exercise with your primary clinical orientation safeguards its therapeutic integrity and supports ethical accountability.

Begin by mapping out your guiding theoretical approaches. For some practitioners, these may include psychodynamic theory, humanistic‑experiential models, cognitive‑behavioural frameworks, attachment theory, or trauma‑informed care. Others may integrate somatic, narrative, or transpersonal perspectives. For each potential exercise, note explicitly why you might use it, the psychological mechanisms it aims to activate, and the anticipated therapeutic outcomes.

For instance, a “visual safe‑place collage” might draw on guided imagery and somatic grounding principles for clients experiencing anxiety or post‑traumatic stress. Its intended functions could include nervous system regulation, promotion of internal resources, and reduction of intrusive imagery. Documenting this rationale not only clarifies clinical purpose but also strengthens your confidence in adapting exercises to different contexts.

Adaptability is vital. A single exercise can have multiple applications depending on the population and goal. A life‑timeline drawing may support grief processing by honouring memories and life phases; for a career‑coaching context, the same structure can highlight personal achievements and future aspirations. Record these variations to make your library versatile and responsive.

Integrating Psychological Theories

Art therapists often draw from a range of psychological theories, including psychodynamic, humanistic, cognitive-behavioral (CBT), Gestalt, developmental, attachment-based, Jungian, narrative, and mindfulness-based approaches. For instance, a psychodynamic approach might utilize art exercises that encourage symbolic expression and exploration of unconscious conflicts, such as creating a ‘dream image’ or a ‘family sculpture.’ Conversely, a CBT-informed exercise might focus on identifying and challenging negative thought patterns through visual journaling or creating ‘coping cards’ with visual affirmations.

The Role of Evidence-Based Practice

In contemporary healthcare, evidence-based practice (EBP) is crucial. For art therapists, this means integrating the best available research evidence with clinical expertise and client values. When selecting or developing exercises, consider whether there is empirical support for their effectiveness in addressing specific therapeutic goals or populations. While direct research on every single art exercise may be limited, the underlying principles (e.g., emotional regulation, self-expression, cognitive restructuring) often have a strong evidence base in broader psychological literature. Regularly monitoring client outcomes and adapting exercises based on observed progress is also a key component of EBP in art therapy.

Practical Application:

- Categorize by Theory: Organize your library by the primary theoretical orientation each exercise aligns with (e.g., ‘Psychodynamic Explorations,’ ‘CBT-Informed Interventions,’ ‘Mindfulness Art’).

- Research Efficacy: Before incorporating a new exercise, conduct a brief literature review to understand its potential benefits and applications, looking for studies on similar art-based interventions or the psychological principles it addresses.

- Reflective Questions: For each exercise, include reflective questions that prompt you to consider: ‘What theoretical principles does this exercise engage?’ and ‘What evidence supports the use of this approach for my client’s goals?’

Practical Strategies for Curating and Organizing Your Library

The most effective art therapy library is one you can navigate instantly, particularly during a client session. Organisational systems should allow you to retrieve, adapt, and implement exercises without interrupting the therapeutic process.

Digital infrastructure is essential for storing templates, step‑by‑step instructions, and handouts. Use folders and subfolders categorised by factors such as:

- Medium (e.g., drawing, collage, painting, sculpture, mixed media)

- Therapeutic goal (emotional expression, perspective‑taking, grounding, identity exploration)

- Session length (brief intervention, 30‑minute activity, multi‑session project)

- Client demographic (children, adolescents, adults, groups, neurodiverse clients)

- Emotional intensity (low, moderate, high)

Complement this with physical resources such as a binder, index cards, or laminated instruction sheets for use when offline or when you need tactile prompts in the therapy space.

Flexibility comes from thoughtful categorisation. For example, tagging an exercise as “high‑intensity trauma processing / mixed media / adaptable for teens and adults” allows you to quickly assess its suitability in the moment. Keep original versions intact, storing adaptations separately with notes on how and why they were modified.

Consider scalability. Your first version of the library may be modest, but a well‑designed structure makes it simple to add new exercises drawn from workshops, supervision sessions, or the latest research. Make updating your library a regular part of your professional practice — perhaps quarterly, in conjunction with supervision or reflective journalling.

Developing a Standardized Template for Each Exercise

To ensure consistency and ease of use, it is highly recommended to create a standardized template for documenting each therapeutic art exercise. This template should capture essential information that allows for quick retrieval and informed application. Key elements of such a template might include:

- Exercise Title: A clear and concise name for the activity.

- Theoretical Orientation: The primary psychological or art therapy theory/theories the exercise aligns with.

- Therapeutic Goals: Specific objectives the exercise aims to achieve (e.g., emotional expression, stress reduction, cognitive reframing, self-discovery).

- Materials Needed: A comprehensive list of art materials required.

- Instructions: Step-by-step guidance for facilitating the exercise.

- Processing Questions: Prompts for post-activity discussion and reflection with the client.

- Variations/Adaptations: Suggestions for modifying the exercise for different age groups, clinical populations, or therapeutic settings (individual, group, family).

- Contraindications/Considerations: Any potential risks or specific client populations for whom the exercise might not be suitable.

- Evidence Base/References: Links to relevant research or theoretical texts supporting the exercise.

- Tags: to facilitate searchability

Organization and Accessibility

The method of organization is crucial for the utility of your library. While physical binders or card systems can be effective, digital solutions offer greater flexibility, searchability, and ease of updating. Consider using cloud-based platforms, dedicated therapy software, or even a simple, well-structured folder system on your computer.

Practical Application:

- Digital Database: Create a digital database (e.g., using a spreadsheet, a dedicated note-taking app like Notion or Evernote, or a simple word processing document) where each exercise has its own entry following your standardized template.

- Tagging and Keywords: Implement a tagging system or use keywords to make exercises easily searchable by therapeutic goal, theoretical orientation, materials, client population, or duration.

- Regular Review and Update: Schedule regular times to review your library, add new exercises, update existing ones based on new research or clinical experience, and remove those that are no longer effective or relevant. This ensures your library remains a living, evolving resource.

- Supervision Integration: Use your library as a tool in supervision. Discuss specific exercises with your supervisor, exploring their application, client responses, and potential modifications. This fosters deeper learning and refines your clinical skills.

Integrating Reflective Practice and Continuous Learning

An art therapy library is not static. Clinical insight, research developments, and reflective practice should continually refine it. Evidence integration begins with sourcing exercises from reliable channels: peer‑reviewed journals, conference presentations, reputable professional bodies, and practitioner networks.

When you introduce a new exercise, treat the first few uses as a pilot. Observe:

- The client’s level of engagement in the creative process

- The depth and direction of the material that emerges

- Emotional or behavioural shifts during and after the activity

- Any resistance, overwhelm, or unexpected outcomes

Document your reflections ethically and securely. This might include session notes about modifications, cultural considerations, or alignment with treatment goals. Maintain confidentiality while ensuring sufficient detail to inform future use.

Evaluation can be qualitative, such as client feedback, therapist reflections, or analysis of thematic shifts in artwork, or quantitative, through appropriate standardised measures. Over time, this reflective‑evidence loop builds a practice‑based evidence base, strengthening the credibility and effectiveness of your library.

The Importance of Reflective Practice

Reflective practice involves actively thinking about one’s experiences, actions, and decisions in a professional context, with the aim of learning and improving. For art therapists, this means reflecting on how specific art exercises are received by clients, what insights emerge from the art-making process, and how the therapist’s own biases or experiences might influence the intervention. This critical self-awareness is vital for tailoring exercises to individual clients and for recognizing when an exercise needs modification or a different approach is warranted.

Continuous Learning and Professional Development

The field of art therapy, like all mental health professions, is constantly evolving. New research emerges, theoretical models are refined, and best practices are updated. To maintain a relevant and effective library of exercises, art therapists must engage in continuous learning. This can take many forms:

- Attending Workshops and Conferences: These provide opportunities to learn new techniques, explore different theoretical perspectives, and network with peers.

- Reading Professional Literature: Staying current with journals, books, and online resources dedicated to art therapy, psychology, and related fields.

- Peer Consultation and Supervision: Engaging in regular supervision and peer consultation offers invaluable opportunities to discuss challenging cases, gain new perspectives on interventions, and receive feedback on the application of art exercises.

- Personal Art-Making: Engaging in one’s own art-making process can deepen understanding of the therapeutic potential of art and foster empathy for the client’s experience.

Practical Application:

- Post-Session Reflection: After each session, take time to reflect on the art exercises used. Ask yourself: What worked well? What was challenging? How did the client respond? What might I do differently next time?

- Supervision Agenda Item: Make your art exercise library a regular agenda item in supervision. Discuss specific exercises, client responses, and explore how to deepen their therapeutic impact.

- Professional Development Log: Maintain a log of workshops, conferences, and relevant readings. Note down new exercises or theoretical insights gained and consider how they might be integrated into your library.

- Personal Art Exploration: Dedicate time to personal art-making, experimenting with different materials and processes. This can inform your understanding of the exercises you offer to clients and spark new ideas for your library.

Business and Ethical Considerations

For those in private practice, your art exercise library is also a business asset. Protect intellectual property by noting the source of each activity and ensuring you have the right to reproduce or adapt it. Where exercises are drawn directly from another practitioner or a published work, give full attribution.

From a risk‑management perspective, always consider the potential psychological impact of an activity. Exercises that delve into trauma or intense affective material should be supported by grounding techniques, safety planning, and informed consent. Your library’s structure should include clear risk indicators for such activities, guiding appropriate use.

Building a library of therapeutic art exercises is a strategic, creative, and ethical endeavour. It calls for an understanding of psychological theory, a commitment to responsive practice, and a disciplined approach to organisation and evaluation. With these three pillars, purposeful alignment, structured accessibility, and ongoing evaluation, your library becomes more than a convenience.

It becomes a cornerstone of your clinical identity which entails a tangible reflection of your values, skills, and ongoing commitment to supporting clients through art therapy.

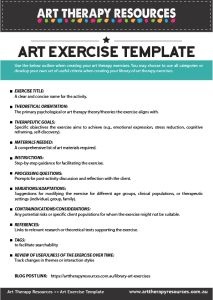

FREE DOWNLOAD: Art Therapy Exercise

SIGN UP below to gain access to our RESOURCE LIBRARY and download the FREE Art Exercise Template.

To assist you in building your own robust library, we have created a customizable Therapeutic Art Exercise Template. This template provides a structured framework for documenting each exercise, ensuring you capture all essential information from theoretical grounding to practical application and reflective questions. Download it today to streamline your practice and enhance your therapeutic interventions!

- Exercise Title: A clear and concise name for the activity.

- Theoretical Orientation: The primary psychological or art therapy theory/theories the exercise aligns with.

- Therapeutic Goals: Specific objectives the exercise aims to achieve (e.g., emotional expression, stress reduction, cognitive reframing, self-discovery).

- Materials Needed: A comprehensive list of art materials required.

- Instructions: Step-by-step guidance for facilitating the exercise.

- Processing Questions: Prompts for post-activity discussion and reflection with the client.

- Variations/Adaptations: Suggestions for modifying the exercise for different age groups, clinical populations, or therapeutic settings (individual, group, family).

- Contraindications/Considerations: Any potential risks or specific client populations for whom the exercise might not be suitable.

- Evidence Base/References: Links to relevant research or theoretical texts supporting the exercise.

- Tags: to facilitate searchability

BUILD YOUR ART THERAPY REFERENCE MATERIALS:

Pin this image to your Pinterest board.

SHARE KNOWLEDGE & PASS IT ON:

If you’ve enjoyed this post, please share it on Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest. Thank you!